To our great delight and surprise, our animated Facility Manager Prototype and respective Blog article was used as demonstration and reference material at UXCamp Europe 2011. In regard of the apparent interest in the topic this article picks up the issue yet again, focusing on scientific considerations of the past years.

Indeed, animations have become an integral part in today’s modern applications, especially the iPhone and Co. Having this said, it astonishes that scientific efforts are still in fledgling stages and that the few existing approaches vaguely draw upon techniques and rules used for cartoon movies. At the same time however, choosing the wrong animation will literally paralyze a User Interface.

Research

The significance of movement as a coding mechanism has been of critical importance to humans since the beginning of time. Their speed and frequency help us with their interpretation and allow the deduction of a respective conclusion. In that they carry a message: a dancing movement certainly implies a very different message as would a hectic or fast one. Heider and Simmel were able to illustrate this phenomenon in the mid-40s, as abstract objects in an animated movie were credited with human characteristics by their viewers.

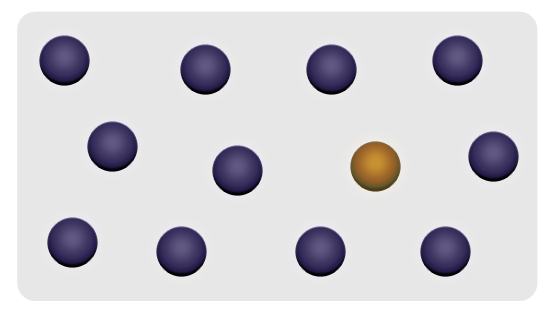

Furthermore, movements evoke orientation reactions and guide perception, even if they just occur in the periphery of the vision (Faraday & Sutcliffe, 1997). It is thereby assumed that the right kind of animation lessens the cognitive burden for the user, since changes are communicated effectively. For instance, this is the case when controls appear or disappear. These changes are apprehended in early stages of perception and are even processed “preattentively” for some part (Bartram, 2001). In essence the term “preattentive” describes a rapid, automatic and parallel form of information processing. A simple example clarifies the phenomenon on a different level: the target in the picture below can be perceived preattentively, as it is characterized by the visual quality yellow.

To speak in terms of an IT-technician, if the hard-drive is our long-term memory with slow but reliable access and the RAM is our short-term memory, which is faster but fleeting, then the graphics card is the counterpart to preattentive processing, as it handles the data incredibly fast without sending it through any of the hardware mentioned before.

Back on topic: it is assumed movement is processed in a similar fashion, even though in this case there are several layers to consider leaving room for discussion. In any case however, it was shown that animations provide efficient “pop out” effects, especially on crowded UIs (Bartram, 2001).

Other interesting approaches consider animations to increase spatial perception of a user. In our natural environment our own movement and that of our surroundings help us to create a spatial model of where we are. In digital environments however animations are supposed to achieve the same effects. The increased orientation also favors memorization and relocation of features or information (Boltman & Bederson, 1998).

Last but not least, being and staying in the flow was discussed, especially in the light of providing smooth transitions when a UI reacts slowly for technical reasons (Huhtala, Sarjanoja, Mäntyjärvi, Isomursu, & Häkkilä, 2010).

Complexity of an Animation

That’s all well and good, but how is an animation supposed to look in order to make use of the advantages outlined above. First of all, one needs to acknowledge animations as the complex phenomena they are, while considering the multitude of factors that influence their design. These factors can be roughly categorized using the three aspects of human, computer and interaction (no pun intended here).

With the human in mind, that is to say the user of a software, expertise and experience with computers and the software itself must be taken into account. By adopting the respective mental model, animations may ease the understanding – in this respect animations of an eBook-reader draw upon the real thing. Admittedly, this point is open for argument. The realistic reproduction (skeuomorph) might lessen innovation, shutting out potentially better ideas from the start. In essence however, it is just about creating believable, natural and “organic” animations, which handle objects on the UI according to their “physical” integrity.

In terms of computing, technical issues play a major part regarding the design of an animation. Important criteria include platform, hardware and size of the screen. Naturally, an animation on a mobile phone will be different from one on a desktop PC, as the different technical environments yield different use cases.

Lastly, the form of interaction will be having a considerable effect on the creation of an animation. For once the context of use has to be clarified. While the area of entertainment allows use of rampant and complex animations, those are a no-go in business applications. Most important however is the reason for employing an animation, in other words the desired effect one wants to achieve. Potential tasks might be “improving orientation” or “delivering additional cues”. Using animations just because you can is reserved to the gaming industry only. When working with UIs the first step to creating a good animation is to define its task.

Motion Design: Design of an Animation

More and more of Centigrade’s customers decide to ask for services in the field of “motion design”, that is the design of an animation in regard to a certain task. The following project for instance uses animation to provide good orientation on the UI despite the limited screen space. In order to achieve this only those controls that are needed in a certain context are shown, while the others stay hidden.

Animation may also be used as a primary design dimension, as shown in the video below. The motion design study in context of a human resource management application raises perception and effect of animations by reducing the visual design. By the use of animations relationships and dependencies are shown to the Human Resource Manager in an understandable and intuitive fashion.

When designing an animation it makes sense to distinguish between macro- and micro-animations, depending on whether they are supposed to accompany a complex screen change or just let a small widget (dis)appear. Apart from that, there is a set of perceptual characteristics or dimensions that define an animation, such as duration, speed, direction, modality, spatial extend synchronization and category. Afterwards it can be fine-tuned by using an easing-function.

At this point, many instructions exist. For example an article on MSDN recommends choosing the shortest route between two spots as animation path. When deleting an item on a Mac OS X however, the animation is presented in an arc. In addition the “genie effect” with a duration of about a second violates the recommendation to keep running times well under 200ms, which is given in said MSDN article. Why is it, that both animations would still be considered good animations (even without taking the assumption that mac users have more time)?

The answer might be this: Apart from making an UI more understandable and smoother, animation can add personality, character and style to a software. A recent study of Parker and Lee (2010) even points out that they possess affective qualities. This is especially interesting against the backdrop of Heider and Simmel’s experiment mentioned earlier and provides a possible and potent reason for the use of an animation: „add personality and increase recognition value”.

So what’s next?

Well, now the motion designer is walking a thin line, between safety and conformity of a one-dimensional, simple and subtle animation and the ambition to convey character and personality. This is exactly the point at which a scientific approach is needed. Many of todays accepted concepts are based on folk psychology or trial and error rather than on empirical research, for example the usage of blinking task bar icons for notification purposes.

It would be particularly interesting to isolate different use cases and interaction schemes and evaluate which type of animations is especially advantageous in certain domains. In that regard, animation vocabularies could be established for different business sectors or the employment of real world metaphors in animations could be explored. On the basis of a well-founded and substantiated framework, the design of an animation would be reduced by several degrees of freedom (and several degrees of insecurity).

As last statement for closing: the specification of design-guidelines is regarded as decreasing artistic expression and creativity most of the times. However, what is truly important in UI design is not creativity per se, but the one which exists inside the given set of reasonable rules in engineering.

References

Bartram, L. R. (2001). Enhancing Information Visualization with Motion.

Bederson, B. (2004). Interfaces for staying in the flow. Ubiquity.

Boltman, A., & Bederson, B. (1998). Does Animation Help Users Build Mental Maps of Spatial Information. HCIL Technical Report.

Faraday, P., & Sutcliffe, A. (1997). Designing effective multimedia presentations. Proceedings of ACM CHI, (S. 272–279).

Heider, F. &. Simmel, M (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. American Journal of Psychology, S. 243–259.

Huhtala, J., Sarjanoja, A.-H., Mäntyjärvi, J., Isomursu, M., & Häkkilä, J. (2010). Animated UI transitions and perception of time: a user study on animated effects on a mobile screen. CHI, (S. 1339-1342).

msdn. (2011). Animations and Transitions. Abgerufen am 29. 7 2011 von http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa511285.aspx

Park, D., & Lee, J.-H. (2010). Investigating the Affective Quality of Motion in User Interfaces to Improve User Experience. ICEC , 67-78.